I really love the book. It’s a great one.

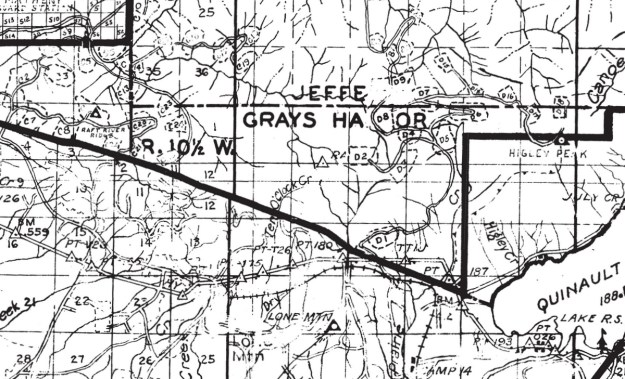

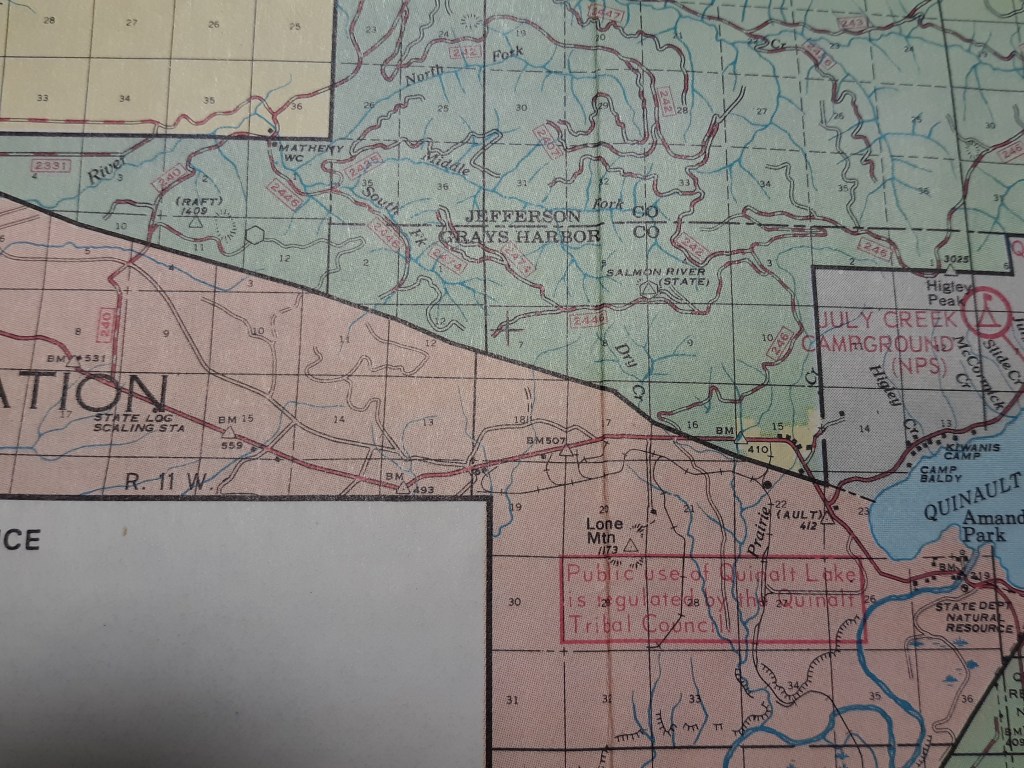

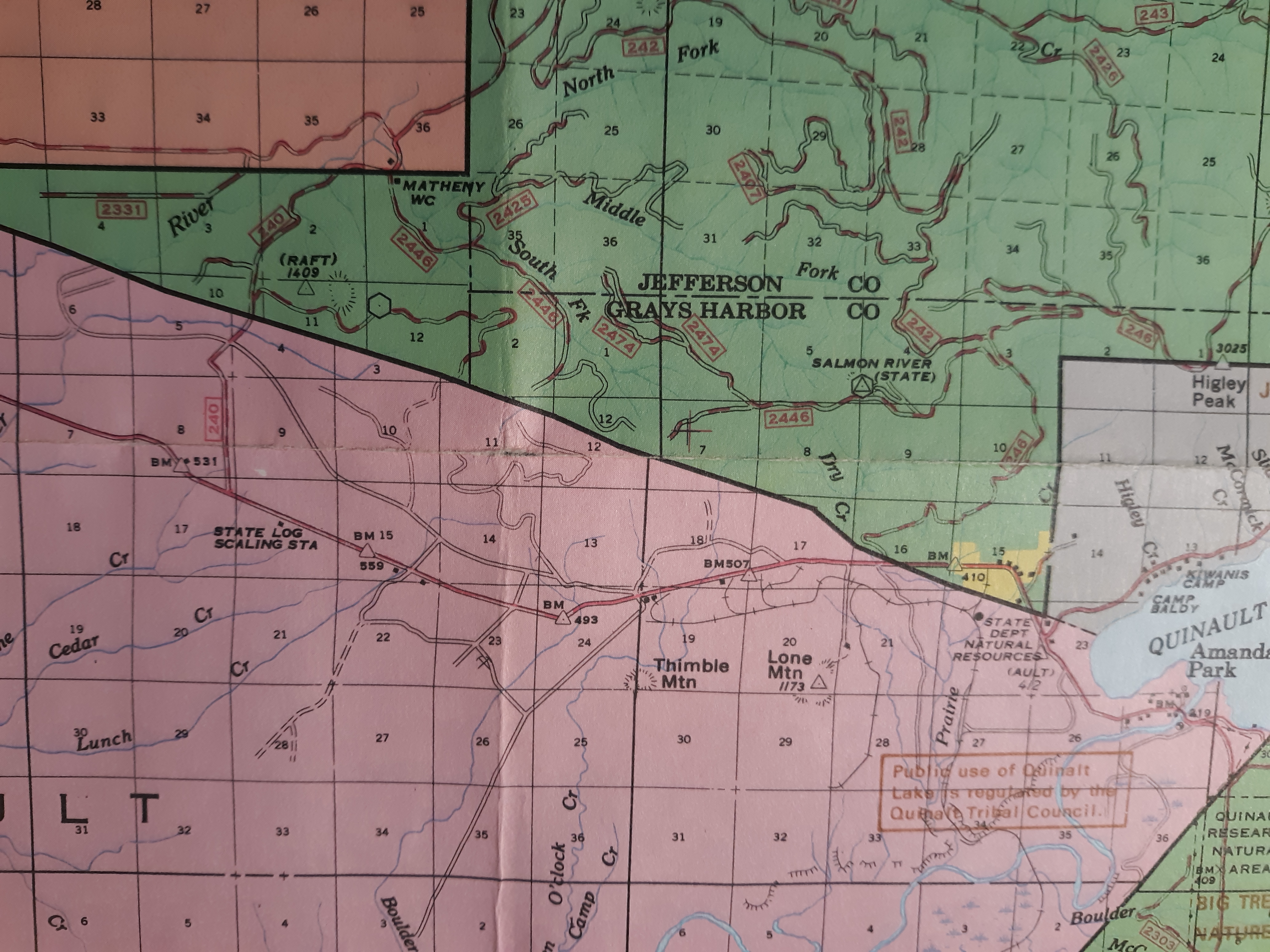

This book is a welcome addition to my collection of Washington hiking and climbing guides. All of the hikes in this outstanding book lead to remote summits that are off the beaten path yet incredibly accessible. The historical research and maps add background and context to the scenic points and how they were important to the region’s history.

–Mike Gauthier, author of Mount Rainier: A Climbing Guide

Leslie Romer’s book brings the fire lookout era to life again, as well as offering wisdom and insight from one who not only has visited the sites but taken the time to observe, listen and learn what nature has to say about the past, the present and the future of the forest. There is a wealth of information, knowledge and thought to be found in these pages.

–Bryon Monohon, Forks Timber Museum Director

If you’re an admirer of Washington’s fire lookouts, seek off-the-beaten path hiking destinations, and have an appreciation for the state’s colorful logging, conservation, and war time history—you’ll want this guide on your bookshelf and in your pack.

—Craig Romano, award winning guidebook author of more than 25 titles

I couldn’t stop reading! Lost Fire Lookout Hikes and Histories: Olympic Peninsula and Willapa Hills is a must-have for anyone interested in fire lookouts, Washington State history and/or hiking. The book combines interesting historic facts with detailed driving directions and trail descriptions.

–Tammy McLeod, creator of Fire Lookouts of the West Coloring Book

Author Leslie Romer not only gives the necessary information needed to visit the “lost” lookouts of Washington’s Olympics and Willapa Hills, she has painstakingly researched and updated lookout histories. I am placing my copy of Lost Fire Lookout Hikes and Histories: Olympic Peninsula and Willapa Hills on the shelf next to my well-worn copy of Kresek’s magnum opus, Fire Lookouts of the Pacific Northwest. That’s where it belongs.

–Keith Lundy Hoofnagle, Former Olympic Fire Lookout and National Park Service Ranger

When it comes to exploring the hills, doing the research and having knowledgeable contacts, Leslie leads the pack. This long-needed guide from her many site visits provides everything you need to have a wonderful fire lookout experience, even if the lookout building is long gone. The guidebook lays out the history, access and route in excellent detail, prompting the reader to want to go out and explore them.

–Eric Willhite, Peakbagger and Fire Lookout Blogger

Leslie Romer performs a major feat of archival research, as well as years of footwork, to come up with this wonderful new contribution to the Northwest’s great-outdoors bookshelf. She spells out exactly how to follow in her footsteps, and she fleshes out the experience with details of both the present plant life and the past—in words and in exhumed photos.

–Daniel Mathews, author of Cascadia Revealed: A Guide to the Plants, Animals and Geology of the Pacific Northwest Mountains

This is a magnificent book, written by an experienced hiker and environmentalist. She has specialized in hiking to old fire lookout sites and has now visited more than 500 sites, most of them in Washington State. The book contains extensive overview of 65 lookout sites in Washington´s coastal region, providing historic background as well as practical information and detailed route maps.

–Bragi Ragnarsson, Professional Hiking Guide, Reykjavik, Iceland

Part hiking guide and part history book, Leslie Romer’s Lost Fire Lookout Hikes and Histories is a richly detailed account of the long forgotten fire lookouts that once dotted the Olympic Peninsula and Willapa Hills. Romer, a backcountry enthusiast, adeptly guides the reader to the lookouts on trails just waiting to be explored.

–John Dodge, author of A Deadly Wind: The 1962 Columbus Day Storm

It is delightful… Leslie Romer makes a difference ⁓ inspiring a search for our history while exploring our beautiful world. May her readers follow her footsteps and find their own paths.

–Molly Erickson, US Forest Service, Retired (44 years)

slope: bladder campion, mosses, and a variety of grasses. We also noticed wonderful patterns in the undisturbed lava. And we observed dark clouds headed in our direction again. Finally the car came into view and we began to wonder if we would reach the car first. We succeeded, but not by much. We jumped inside and changed out of our hiking boots as the rain began its tattoo on the roof.

slope: bladder campion, mosses, and a variety of grasses. We also noticed wonderful patterns in the undisturbed lava. And we observed dark clouds headed in our direction again. Finally the car came into view and we began to wonder if we would reach the car first. We succeeded, but not by much. We jumped inside and changed out of our hiking boots as the rain began its tattoo on the roof.

The trails became less developed the farther we went. It seemed they were used mostly by sheep and occasional birdwatchers. We saw swans on the water, heard and finally spotted a pair of loons. Among the grasses we observed pipits and wagtails, too. Occasionally we walked through a cloud of midges, but the bugs were cooperatively stationary, so they did not bother us much at all.

The trails became less developed the farther we went. It seemed they were used mostly by sheep and occasional birdwatchers. We saw swans on the water, heard and finally spotted a pair of loons. Among the grasses we observed pipits and wagtails, too. Occasionally we walked through a cloud of midges, but the bugs were cooperatively stationary, so they did not bother us much at all.